Ahh… I’m finally nearing the stage of the dissertation where I can begin to have some fun (not that writing hasn’t been a joy in its own special way). Tonight, I experimented with Photoscape in drawing roads and place names on an image of a faded map (likely from the late Edo period) of the Togakushi region. I’m hoping it will help readers get a visual of the sites I discuss in the chapters. Here are the preliminary results. (Original image courtesy of the Shinshū Digikura digital archive.)

Tag Archives: Togakushi

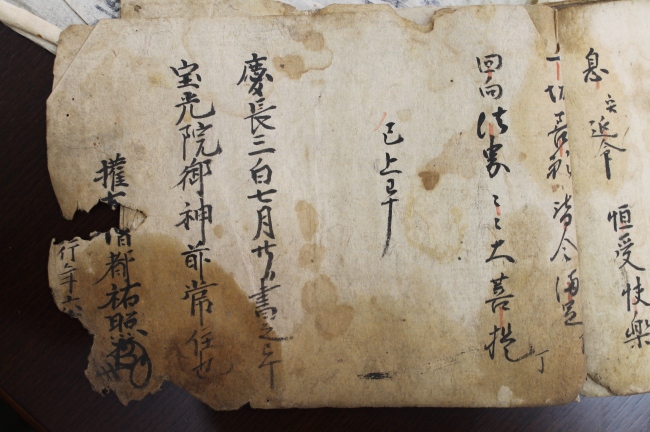

Edo period texts from Togakushi

After about a year of requesting to view archives at Togakushi Jinja that are relevant to my research, I finally finagled my way into seeing a number of them on my last visit before returning to the States.

These documents were archived and catalogued in the 1960s and have since sat in a storage shed at the shrine, for the most part untouched. A huge thanks to local scholar and priest, Futazawa Hisaaki 二澤久昭, who spent hours rummaging through them (apparently in disarray) and then further hours helping me to decipher some of them. Futazawa-San by the way, descends from one of the Edo period cloisters (shukubō 宿坊) and has converted his into a wonderful Japanese inn and serves delicious food.

Here are samples of some of the texts we checked out.

These first three images are from a text titled the Dai hannya hōsoku 大般若法即 (Regulations of the Great Heart). I haven’t looked closely at it yet but the title refers to Prajñāpāramitā literature and the nature of the text is ritualistic. It’s not listed in the catalog so was a surprise to find.

The date on the last page here reads Keichō 慶長 3, or 1598.

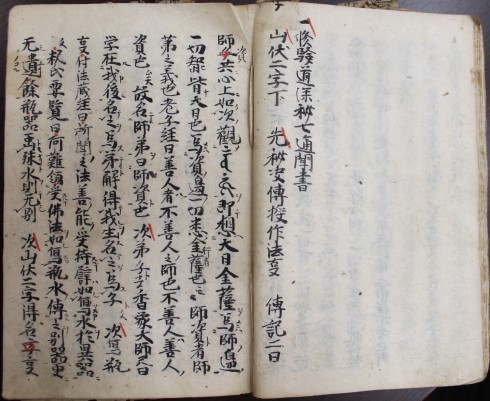

The two volume set below, titled the Shugendō hiketsu hōsoku 修験道秘決, was the most exciting text of my find and will probably factor into my assessment of Shugendō at Togakushi during the Edo period. Its undated but based on the content, must have been composed in a hundred year period between the 1720s and 1818.

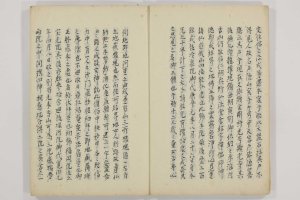

This is a registry of Togakushi-san’s from 1814 (Bunka 11). It lists 32 Shugendō households affiliated with the mountain at this time.

The information for each yamabushi 山伏 presented here includes his rank, year of birth, year of tonsure, temple location and name, and his affiliated Togakushi cloister.

Often these yamabushi would serve as disciples to the priests of the mountain and eventually succeed them. For this reason, Shugendō became central to the identity, practices, and thought of Togakushi during the Edo period (I argue), despite its subordination to the Tendai Buddhist institution at this time.

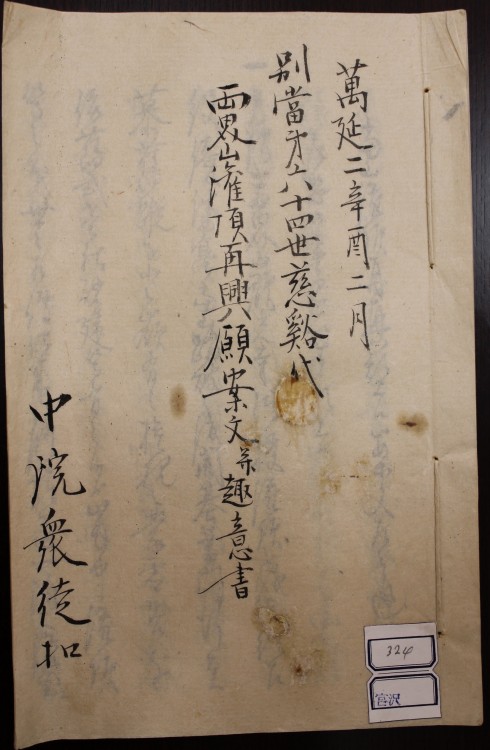

At the end of the Edo period, there was a major drive at Togakushi to strengthen its branch of Shugendō. This next text, titled the Togakushi-san Kenkōji kanjō saikō gan 戸隠山顕光寺灌頂再興願 was composed by the mountain’s chief administrator (bettō) in 1861.

The effort only lasted a few years, as the temple-shrine complex was converted into a national shrine at the beginning of the Meiji period.

説話・儀礼対象から主神への変遷―戸隠山の九頭龍の形成をめぐって

Below is a presentation I recently gave at Keio University on the nine-headed dragon (Kuzuryū) of Mt. Togakushi. Sorry English readers (its mostly in Japanese). The title translated though, is “From narrative and ritual object to resident deity: Tracing the formation of the nine-headed dragon at Mt. Togakushi.” Textual passages are also translated into English and there’s a brief conclusion in English at the end.

この間、慶應義塾大学戸隠山の九頭龍について発表しました。レジメは以下の通りです。

説話・儀礼対象から地主神への変遷―戸隠山の九頭龍の形成をめぐって

第一 アジアにおける龍の信仰

一般的な特徴:水の管理(雨、災害など)、地主神、佛法の保護神、王権の象徴など

生息地(habitat):池、川、海、山、天

両面性の特性:

| 危険的 | 保護的 |

| 水に関する災害(大雨、洪水) | 雨を与える(水不足、農業などに対する) |

| 激しい・不安定的な状態 | 郷土、佛法、王権など |

佛教関係:

1)密教儀礼:雨乞い(rain-making rituals)、曼荼羅や印相(mudrā)などに関連する。

2)説話・物語:釈迦牟尼佛(Śākyamuni Buddha)の人生の物語を始め、法華経にある説話(八大龍王、龍王女の成る佛)、寺社の縁起などとよく結びついている。

日本の場合:

インド(nāga=龍)を始め、中国・朝鮮文化の佛教を通じて、龍・龍王信仰が日本に到達した。

最も早い出現:九世紀に、龍信仰が展開するとともに真言系の僧侶は密教儀礼を通じて龍王に雨を祈った。平安公家・貴族に対して、平安京にある天皇の御所近くの神泉苑や奈良県の室生寺を中心に善女龍王に関する縁起を造り、様々な密教的な雨乞いを行っていた。(Ruppert、2002年)

それ以降、全国では龍・大蛇・鬼などが徐々に各地の寺社(特に山の中心)の縁起に含められた。(内藤正敏氏、2009年)

第二 九頭を持つ龍(Nine-headed dragons)

佛教典:

- CBETA大正新脩大藏經(漢語で書かれたインドから中国・朝鮮に渡った佛典):「九頭龍」は34個の検索結果があった。

- SAT大正新脩大藏經(大正大藏經+日本の佛典):「九頭竜」・「九頭龍」は69個の検索結果があった。

- 法華經文献:法華經には、八大龍王が現れるが、九頭龍はその中ではない。その一方、以降の法華經に関する文献(論、義釋、伝記など)によく現れる。

- 中国の天台系:『法華傳記』(唐朝前半)、『止観輔行傳弘決』(8世紀)、『佛祖統紀』(1269年)など

*以上の中国で書かれたテキストは唐時代以降に著作される。そして多くの場合では、釋智璪という僧侶の伝記に結びついたが、寺社縁起とは関係なさそうである。

密教儀礼:

- 「九頭龍印」という印相:大日經文献、台密のテキスト(『行林抄』など)

- 曼荼羅に位置している:『法華曼荼羅威儀形色法經』、『胎藏入理鈔』など

- 雨乞い:『行林抄』1152 (仁平 2年)

日本における寺社縁起:

| 地名 | 最初の文献 | 文献年間 | 龍の漢字 | 関連する行者 | 関連する佛 | 宗 |

| 白山 | 『泰澄和尚伝記』 | 12世紀後半[2] | 九頭龍王 | 泰澄 | 十一面観音 | ? |

| 大峯(水天嶺) | 『大菩提山等縁起』 | 1152 (仁平 2年) | 九頭龍王 | 無 | 無 | 不明 |

| 箱根 | 『筥根山縁起并序』 | 1191 (建久2年) | 九頭毒龍 | 萬巻人 | 無 | 不明 |

| 阿蘇山 | 『彦山流記』 | 1213年 (建保1年) | 九頭八面大龍 | 臥驗 | 十一面観音 | 天台 ? |

| 戸隠山 | 『阿娑縛抄』 | 1279 (弘安2年) | 九頭一尾鬼 | 學問修行者 | 聖観音 | 天台 |

以上の縁起の共通点:

- ほとんどの縁起ではその龍が修行している行者の前に出現する。

- 観音菩薩と関連するケースが多い。九頭龍のように数多くの頭があるので、イメージ的に想像されたのか?

- 全部が山岳寺社の縁起である。

- 12世紀後半に九頭を持ち龍が突然に登場し、流行(龍行か?)していた。

- 九頭龍の名前はまだ既定されていない。むしろ「九頭」が名前よりも記述ではないか。

第三 縁起に現れる龍から地主神への変遷

資料1:「戸隠寺略記」、1279年(弘安2年)、『阿娑縛抄』、227巻の第200巻目の「諸寺略記上」、承澄編(1205–1282;延暦寺僧)

In 849 (Kashō 嘉祥 2), a learned practitioner (gakumon shugyō sha 學問修行者) spent seven days on Iizuna-san 飯縄山. Facing west toward a great peak, he prayed (kinen 祈念). He threw a single-armed sceptre (dokko 獨鈷?)[3] that took flight and then fell. He went to go see it. [It had landed] at a great stone cavern. At that site he chanted the Lotus Sūtra. During this time, a foul-smelling wind was exhaled from the south. A nine-headed, single-tailed oni (kuzu ichibi ki 九頭一尾鬼) arrived [and said,]

“Who chants the Lotus Sūtra? Even though I had no intention of harm (mugaishin 無害心), when I came to listen to those who recited it (chōmon 聽聞) in the past, they ended up dead after my noxious vapors reached them.

“I was the former administrator. I lived in greed and desire, carelessly using the donations of the faithful (shinse 信施). As a result, I received this body. This place has been destroyed and toppled down over forty times. I rely on the virtue (kōdoku 功徳) [of listening to you chant the Lotus Sūtra] and thus should able to attain awakening.”

Gakumon replied, “An oni hides its form.” Following these words, the oni returned to its original place. In that place, which is named “the dragon’s tail,” [the oni] entered into seclusion and sealed shut the door of the stone cavern.

From within the ground, a great voice chanted, “Take refuge in the assembly in which [I,] the honored Shō Kanjizai 聖観自在 [Shō Kannon] eternally reside; as a great avatar, [I] provide benefits to living beings at the three sites” (南無常住界會聖観自在尊三所利生大権現聖者).

This mountain is known as the temple of “the door [behind which one] hides” (Togakushi-ji 戸隠寺), because it conceals the dragon-tailed oni. The door of the stone cavern thus led to the establishment [of the temple]. It is also said that the from Mt. Iizuna, the [mountain’s] form resembles a door…

- 「學問修行者」というのは、おそらく人名ではなく、ただ学問や修行する人と指摘している(鈴木正崇氏、2013年、250–251頁)。という事は、当時、開祖という概念は薄いようである。

- 同じように(そして上記の5個の縁起のように)「九頭一尾鬼」というのも一般名称ではないか。

- この龍的な鬼が「前の別当」というのは、戸隠山の歴史を作ったが、良いイメージではない。鬼の存在をはじめに、現在の客姿格好は以前の悪い生活の業罰である。つまりこの段階では、九頭一尾鬼=主神というのはまだ微妙ではないか。

- 聖観音と九頭一尾鬼との関係は曖昧であり、神仏習合(本地垂迹)ははっきりしていない。

資料2:戸隠山顕光寺流記(並序)(以下『流記』と略す)、十穀僧有通編、1458年(長禄 2年)

英訳の節

There was a man known as Gakumon gyōja 學門行者. The mysterious profundity of his original nature (honji 本地) and his rank among the worthies (son’i 尊位) is difficult to estimate. He had accomplished all the practices. Embracing the bright moon, he ventured through the vast night. Replenished by the morning sun, he gazed in all directions (meiku 迷衢). His wisdom and practice was extremely great and his virtue and efficacy (in the magical arts) (tokugen 徳験) was superior in the world. He established a temple (garan 伽藍) in every land. He spread benefits (riyaku 利益) throughout the Dharma realm (hokkai 法界). It is said that his life ended by ascending into the sky without a burial. Thus he is regarded as the [response] body of the honored Śākyamuni and a sympathetic transformation (ōke 應化) of Kannon.

In the beginning, the gyōja said, “I want to restore [the practices of] this mountain.” In the middle of the third month of the third year of the Kashō 嘉祥 (850) era, under the reign of Emperor Ninmei 仁明 (810–850, r. 833–850), he began by climbing [the neighboring] Iizuna-san 飯縄山. [Iizuna] is a high marchmont that soars into the milky way (ginkan 銀漢)—its white summit contrasting the azure sky (hekiraku 碧落). Imprisoned (katai 牢) demons and ghosts (chimi 魑魅) crisscrossed [its slopes]. There was no trace of human paths. Inquiry into its ancient past [reveals that] it had never been scaled. The snow was deep and there were precipitous cliffs. Amidst the clouds, fog and thunder, he lost his way and was unable to ascend. He retreated to the midway point (hanpuku 半腹) [of the mountain]. As an offering to the various deities and spirits, he recited scriptures and chanted dhāraṇī (ju 咒). Tearing up [a section of] his robe (resshō 裂裳; Skt. bimbisāra), he wrapped his feet [with the cloth]. He was ready to discard his life and in his commitment to the way. Making a stern vow, he announced, “I humbly request that the benevolent deities [of this mountain] increase my power, that the heavenly dragons roll up the mist, and the mountain demons (sanmi 山魅) guide me. Please help me realize my goal! If I fail to reach the summit, I will not achieve awakening (bodai 菩提).”

Having produced such a vow, he treaded across the dazzling white snow and ascended [through] sparkling (saisan 璀璨) green leaves. Finally, exhausted and depleted of energy, he could see the summit. Appraising [his whereabouts], he [realized that he had] suddenly entered the Milky Way (unkan 雲漢). Foregoing a taste of this marvelous paradise, he found a divine cave. Elated and awestricken, he found it difficult to keep his mind (shinkon 心魂) tranquil.

For a short while, he gazed about the four directions. From the southeastern foot of the mountain, vast plains unfurled with grasses and trees (sōmoku 草木). Looking out in the distance, he saw the golden swells and silver whitecaps (ginpa 銀波) of a great, flowing river submerged in [i.e. reflecting the] azure sky. There was the faint wake of a crossing vessel. To the northwest were narrow and precipitous ravines and a long and hazardous [ridge line] of mountains laced in deep snow and flowers of the five colors (gosai 五彩). The birds cried out in cold (inkan 咽寒) throughout the day (rokuji 六時). The green canopies of thousand year-old pines and spruce tilted toward the valleys. Deep blue-colored [two-story] manors (konrō 紺樓), surrounded on all sides by cypress and mandarin trees (kaisō 檜楱), towered above the boulders. Gazing across [the entire vista], four mountains streams [are visible]. This divine splendor was vast.

Amidst an abundant sunset, [Gakumon] performed a divination in the western cave. He prayed and repented, “Now sitting on a cornelian seat in this practice site, having arranged incense and flowers [as an offering to the Buddha], and performing chants, I see myself as an śrāvaka (shōmon 聲聞). ” Then he hurled a vajra sceptre (kongō sho 金剛杵) and made the following vow: “From henceforth, may Buddha’s Law (Buppō 佛法) prosper and may living beings find fortune on the ground from where light emanates.”

Then flying [through the air], the mallet swiftly crossed a distance of over one hundred chō 町. A hunter was there. Frightened by the light of the mallet, he quickly fled and emerged [before Gakumon]. [Gakumon] received him and prepared to tell him about the event:

“I will inform [you] with these words: That hunting ground is now a hunting ground that defends the Dharma (gohō 護法).”

[Gakumon] went to go visit the light of the mallet. At the cave [where it landed], he wished to bring forth the resident deity (jinushi 地主). As he prayed (kinen 祈念), a voice came from the depths of the ground. The loud voice chanted,

“Take refuge in the eternally-abiding assembly of the realm: Shō Kanjizai 聖観自在 (Shō Kannon; Noble Avalokitêśvara) of Great Compassion and Sympathy and the origin bodies of the four sites. The avatars of the three sites radiate light and provide comfort” (南無常住界會大慈大悲聖観自在四所本躰、三所権現放光與樂). The voice ended by saying, “The light of Shō Kannon’s image radiates [Kannon’s] noble form from afar. From the luminous seats of a single lotus plant with four pedestals emerge (yūshutsu 湧出) Shō Kannon, Senjū 千手 [Kannon], Shaka 釋迦 (Skt. Śākyamuni), and Jizō 地蔵 (Skt. Kṣitigarbha).” As joyful tears streamed down, [Gakumon] lowered his head in deep devotion (katsugō 渇仰) and performed chants (hosse 法施) at the site.

That night a foul-smelling wind was exhaled from the south. A nine-headed, single-tailed dragon (kuzu ichibi ryū 九頭一尾龍) arrived and said,

“A joyous practitioner arrived at this cave, chanting and rattling (shindoku 振讀) his staff (shakujō 錫杖). By repenting the six root [senses] and practicing the four [types] of tranquility (shi anraku gyō 四安楽行), the poisonous vapors (dokuke 毒氣) have all been vanquished and there is no longer any obstructions (gai 害). You immediately receive me, [so] I will give you the full account (zengo 善語).

“This mountain has been destroyed over forty times. I have engaged in temple duties seven times. The last administrator, Chōhan 澄範, was me. Because I carelessly used the possessions of the Buddha (butsumotsu 佛物), I received this serpent-like body (jashin 蛇身). From many eons up until the present, I have been hindered by the karma (gōshō 業障) of these [dragon] scales (uroko 鱗). I arose when I heard [your] staff and [chanting] Dharma voice (hōon 法音) and obtained liberation (gedatsu 解脫). You must maintain an awakened state of mind (bodai shin 菩提心) and quickly build a great temple (garan 伽藍; Skt. saṃgha-ārāma).”

阿娑縛抄と比較すると、戸隠山の開祖や地主神の輪郭が完全に創られた。

- 一般的な「学問」を名前の「学門」と取替え、彼の伝記も創造され、修行や活動を詳しく伝える。

- 竜的な「鬼」から「地主」の「九頭一尾龍」になる。

- 九頭龍の話の内容は『阿娑縛抄』の話と非常に似ているが、『流記』に入っている以上の節の後に「九頭権現」や「九頭龍権現」と呼ばれる。その節では、「九頭権現」の多彩的な特徴や利益が詳しく説明される。その中で、大辨功徳天(弁財天)の垂迹になったり、佛性や世尊の智恵を持ったり、色々な現世利益を与えたり、法華経である龍女に成ったりしている。しかし気になるのは、その長い話の中では、水神としての説明は一切現れない。その一方、江戸時代に渡って雨乞い、瀬引き、出水の祈禱のような儀礼が密接に結びついていく。そしてその時代になるとともに戸隠山の九頭龍が全国に広がり、その結果、戸隠の代表的な特徴になる。

終りに

九頭龍が戸隠山に到達する前、中国の唐・宋朝や日本の鎌倉時代初期に様々な説話や密教儀礼で流行しているが、当時の存在は以外に抽象的であり、地主神とは言い難い。しかし戸隠山の例を挙げると、時代が流れ徐々に地元の地主神に変遷する事が分かる。

その過程では、文学や密教の世界に入っていた抽象的な物が具体的な神に変化した。その両面性は、幅広い(東アジアの)思想・儀式が各地に到達すればするほど地元的な神に変形される。特殊な神になると同時に、その場所の霊性や名声が発生するのではないか。

(Before its arrival to Togakushi and other sites around the Japanese archipelago, the nine-headed dragon in East Asia exists among esoteric rituals and legendary anecdotes. In this realm, Kuzuryū is situated in the abstract, detached from place and identity. Its title remains more descriptive than nominal. Only when the dragon arrives and gains traction at a specific sites such as Mt. Togakushi does it evolve into concretized deity, Kuzuryū. This residence and ‘precipitation’ of benefits at the mountain simultaneously becomes instrumental in the production of Mt. Togakushi, itself, as a respected numinous and powerful site.)

文献

Bloss, Lowell W. 1973. “The Buddha and the Nāga: A Study in Buddhist Folk Religiosity.” History of Religions 13, no. 1: 36–53.

Chinese Buddhist Electronic Text Association (CBETA).

Cohen, Richard S. 1998. “Nāga, Yakṣiṇī, Buddha: Local Deities and Local Buddhism at Ajanta.” History of Religions 37, no. 4: 360–400.

Hayashi Minao 林巳奈夫. 1993. Tatsu no hanashi: Zuzō kara toku nazo 龍の話 : 図像から解く謎. Tōkyō: Chūō Kōronsha 中央公論社.

Hongō Masatsugu 本郷真紹. 2001. 『白山信仰の源流』. Kyōto: 法蔵館.

Ikegami Shōji 池上正治. 2000. 『龍の百科』. Tōkyō: 新潮社.

Naitō Masatoshi 内藤正敏. 2009. 「戸隠山の鬼―都市の異界と山の異界」. 『江戸・都市の中の異界』. 民俗の発見 IV. Vol. 4: 271–311. 法政大学出版局.

Ruppert, Brian O. 2002. “Buddhist Rainmaking in Early Japan: The Dragon King and the Ritual Careers of Esoteric Monks.” History of Religions 42, no. 2: 143–174.

Suzuki Masataka 鈴木正崇. 2013. 「中世の戸隠と修験道の展開―『顕光寺流記』を読み解く」. 『異界と常世』. Pp. 239–330. 楽瑯書院.

Visser, M. W. de. 1969 (1913). The Dragon in China and Japan. Wiesbaden: Sändig.

Yoshida Kazuhiko 吉田一彦. 2012. 「宗叡の白山入山をめぐって:九世紀における神仏習合の展開(一)」. 『佛教史研究第五〇号抜刷』.

Criticizing Female Exclusion in Fifteenth Century Japan

Part of my research this year has been devoted to a text entitled The Transmitted Account of Kenkō-ji of Mt. Togakushi (Togakushi-san Kenkō-ji ruki 戸隠山顕光寺流記), compiled by the monk, Jikkokusō Ujō 十穀僧有通, in 1458.

Among the many vivid aspects it provides on the religious culture at Mt. Togakushi in the mid-fifteenth century, a passage I came across on the mountain’s practice of nyonin kekkai 女人結界 (a boundary prohibiting women) especially sparked my interest. With some help from my research advisor, Suzuki Masataka (who’s written extensively on the practice) and medieval Buddhist scholar, Iyanaga Nobumi, I came up with a translation for the following passage:

“On the twenty-sixth day of the eighth month of the first year of the Kōhei 康平 era (1058), during the reign of Goreizei-in 後冷泉院, a bright light was radiating out from atop a giant tree fifty cho 町 from Honnin [now Okusha of Togakushi-san].[1] It seemed like a mysterious and unusual living being. The image was that of a divine true body (mishōtai 御正躰).

At that time, there was a young girl of twelve to thirteen years of age in such mental and physical agony that she passed out on the ground. When asked why, she said, “I am the avatar of Jizō 地蔵, the greatest of the three avatars of this mountain, who stands on the left side.[2] That area is a bordered land (kekkai chi 結界地), upon which the trace of women has been removed. Because this defies the Buddha’s orders and ignores his original vow, the benefits of conversion are shallow and scarce. Please erect a building in this place and have me installed.”

Many had their doubts. They insisted that if this was really the divine oracle [of Jizō], then have [the bright light] moved into the sleeve of someone among the priests and laity. Then, it flew down into the sleeve of a śramaṇa among them who had great faith. He worshiped it, [making it] the site of the honored form of the bodhisattva Jizō. Not moving for days, he built a shrine with an attached hermitage. It became a hut in which to pursue the Dharma.

The place where the divine true body [of Jizō] flew down is called Fushigami 伏拝. The temple was first named Fukuokain 福岡院 and later became known as Hōkōin 寶光院 [now Hōkōsha of Togakushi].”

The alleged tree at Fushigami where a bright light radiated from above and a young girl below fell under the possession of the bodhisattva Jizō (though this tree was probably planted later – Edo period?).

Nyonin kekkai became widespread among sacred mountains in the medieval period so it’s no surprise that the practice was adopted at Togakushi-san as well. What is fascinating here is the apparent critique of it at Togakushi in the comment–voiced by Jizō–that it defies the Buddha’s vow (it’s said that Sakyamuni welcomed both men and women into the sangha). As a result, conversion to Buddhism at the mountain provides limited benefit.

Is this Jikkokusō Ujō’s own opinion inserted into the text or does it reflect a wider spread sentiment? Whatever the case, its uncommon to see a critique of the practice coming from within a religious community in premodern Japan. Max Moerman (Localizing Paradise, 2005) discusses other examples, but this one seems particularly pronounced.

Fushigami (literally, to “lie down and worship”), an allusion to the Kumano site of Fushigami, is marked to this day on the old path (古道) between Togakushi’s Hōkōsha and Chūsha shrines. Given the geography of the mountain, this would mean that Hōkōin accepted women while the temple complexes of Chūin (now Chūsha) and Okuin (now Okusha) remained off-limits at this time.

The boundary was later moved in 1795, as evident from an engraved stone marker still standing in between Chūsha and Okusha. (Here’s a Japanese map of the shrines of Togakushi.) The practice was abolished in the Meiji period.

It’s anyone’s guess as to why the boundary was moved between the medieval and early modern periods. The erection of the stone nevertheless, suggests that the rule may have not been strictly enforced up until then. Why after all, reestablish a rule if no one is breaking it?

The ume may be blossoming in Tokyo right now, but it was still snowing in Nagano yesterday.

For those relishing the spring weather this weekend but saying farewell to the ski season, here are some bittersweet photos from a recent Togakushi trip. Given its proximity to Japan’s inland sea, the area gets dumped on by massive amounts of snow each winter.

Locals call the snow mahō no konayuki (which translates into something like “witchcraft powder”) for two reasons: the snow that falls on the range comes as light, fresh powder (optimal for winter sports); and the high quality of the snow is often attributed to Kuzuryū.

Kuzuryū (literally, nine-headed dragon) is the resident deity of the Mt. Togakushi. As a dragon, it has been long worshiped for its control of water – ranging from rainfall for crops to flood prevention. Thus, it comes as no surprise that Kuzuryū is now prayed to for a solid base of powder on the ski slopes each year. For just as the community’s economy was long dependent on agriculture, now it relies on revenue from visiting skiers and snow boarders.

(Click photos to go to gallery mode.)

- View of the Togakushi range (L to R): Nishidake, Togakushi, and Takatsuma

- Izuna on the opposing side

- Wind swept summit

Takaosan

Last month, I posted pictures of the autumn foliage at Mount Togakushi, which rises to 1904m (6246). For the lower Mount Takao though, the maples were peaking this past week. Only an hour west of Shinjuku on the train, I decided to head for the hills.

Not only were the colors beautiful, but the religious landscape of Mount Takao is fascinating as well. Dotted with statues and shrines devoted to an assortment of buddhas, bodhisattvas, gongen and fabled priests, Takoasan’s vibrant mix of practices and beliefs (mostly Shingon Buddhist and Shugendō) is on full display as one hikes up the peak. Here are some images from the mountain.

- This is the traditional entrance to the mountain. Its now known as the Trail 1 (1号線) and takes you along the major temples and shrines of the mountain. Prepare for crowds on weekends and during autumn foliage. The sign reads, [the temple of] Yakuoin of Mount Takao.

- Sitting opposite the sign is Fudōin 不動院, the entrance temple to the mountain.

- A shrine for Jinben daibosatsu 神変大菩薩. Jinben is the deified En no Gyōja, the semi-legendary seventh century founder of Shugendō.

- A mountain bodhisattva.

- Iizuna gongen, the main deity of Takaosan, stands in the center, attended by his tengu retinue. Iizuna comes originally from Mt. Iizuna of the Togakushi range in Nagano Prefecture, though also has roots back to the Indian deity, Dakini. Under Japan’s complex system of honji suijaku 本字垂迹, whereby a powerful buddha or bodhisattva appears as a local god, Iizuna likewise appears as the local manifestation of a disguised, greater being. According to the mountain’s origin account (engi), Iizuna first appeared in the dream of a 14th century Shingon monk who had come from the Kyoto temple of Daigoin 醍醐院. At Takaosan, Iizuna is believed to assist humans in the form of the god, Fudō myōō (indicative of the sword, rope and flames), who likewise appears as the cosmic buddha, Dainichi 大日. This puts him in the unusual position of appearing as an appearance (Fudō) of no less than Dainichi, who is supposed to encompass all aspects of the cosmos (an existential pickle to then have a local manifestation). That aside, one can find statues of all three, as well as Iizuna’s retinue, along the traditional route up the mountain.

- In 1903, a Shingon priest had just finished the 88 temple henro 遍路 (circuit) of Shikoku. Inspired, he established a miniature circuit on Takoasan, which he marked with 88 small buddhas along the way. Here is a small statue of Dainichi as one of them. They all look identical but have different titles inscribed.

- Daitengu 大天狗, one of Iizuna’s attendants/protectors. The long nose is characteristic of most tengu, as are the wings (though only for certain types of tengu). He is cloaked in the garb of a yamabushi (practitioner of Shugendō), whose mysterious mountain existence sometimes gave way to rumors of being part tengu.

- Kotengu 小天狗, Iizuna’s other attendant, takes a menacing pose opposite Daitengu.

- Crowds passing through the entrance gate (Niōmon 仁王門) to the main temple of Yakuōin 薬王院. (This was on a Thursday, so beware of weekends.)

- Yakuōin’s Main Hall. Visitors light incense and fan the blessings of its smoke toward themselves as they pass by.

- A carved dragon by the entrance of the Main Hall.

- Kukai 空海, sitting atop a lotus blossom, bears the features of a buddha in the image. Given the mountain’s Shingon heritage, numerous statues of the school’s founder can be seen along the paths.

- Inari 稲荷 foxes are placed by patrons on rocks beside a small Inari shrine. Inari shrines are ubiquitous across the country but especially relevant here, where the fox was often paired with the animal-like Iizuna in popular ritual.

- A Shingon priest performs a goma fire ritual inside Fudōin 不動院, a small goma hall behind the main temple complex.

- The view from the summit. On a clear day, Mount Fuji can be seen off to the right.

- Wet leaves along the path down.

- A takigyō 滝行 (waterfall practice) site devoted to the Shugendō deity, Fudō myōō, near the base of the mountain (trail number 6). Practitioners of Shugendō chant and perform mūdra under the freezing waterfall. The site is off-limits except to practitioners during designated ritual times.

Access: Mount Takao can be easily reached from Tokyo (Shinjuku) via the regional train system. Click here for details on transportation and hikes. The station, Takaosanguchi, places one about ten minutes’ walk from the entrance to the peak. There are lots of cool shops and eateries on the way to the base.

There are lots of trails, so choosing can be a little difficult. My suggestion: take numbers 1 or 2 in order to pass by all the temples and shrines on the way up. These courses more or less follow the traditional route up the mountain. For something off the beaten path that skips the crowds, opt for the Inarisan 稲荷山 course or number 6 (though its oddly closed to downhill traffic for certain seasons) on the way down. There’s also a cable car for slackers who want a ride halfway up ; )

Either way, for those in Tokyo looking for a bit of natural respite, Takao’s a must.

Edo period ofuda

I stumbled upon a trove of Edo period ofuda 御札, or protective talisman, while searching through archives at the Nagano Prefectural Historical Museum last week. While some may have been purchased at a temple or shrine, others were likely distributed by oshi (pilgrimage guides) to their patrons, who may have lived far from the site.

Ofuda were generally hung inside the household in order to provide protection from burglary, natural disasters, and so forth. They were mass-printed on woodblock and often bore the stamp of the associated temple or shrine. The images and character styles themselves are quite beautiful.

- This appears to be another ofuda of the same oshi.

- Protective ofuda associated with Mt. Ontake and displaying the image of a fox. These may have been distributed by a particular oshi (pilgrimage guide).

- Daikoku tenjin 大黒天神, often one of the Seven Lucky Gods of Japan.

- An ofuda for the sub-temple of Wagōin 和合院 of Kongōbuji 金剛峰寺 of Mt. Koya. Likely Kukai seated here holding a vajra.

- Another dharani, perhaps with a scriptural translation in Chinese on either side of it?

- A protective shrine ofuda with the title of the Heart Sutra (大般若).

- Cool script! Not sure what it reads.

- A Sanskrit ofuda. Any Indian specialists out there? For Japanese purposes, there may be no inherent meaning in the reading, but rather potency in the letters themselves. This may be a dharani that was recited.

- A nenbutsu protective ofuda

Autumn foliage at Togakushi

Happy Autumn! Here’s a bit of foliage from Mt. Togakushi this past week.

- The torii below the Chusha shrine. (Click to enlarge.)

- One of many small shrines that dot the landscape around Togakushi.

- The steps up to Chusha.

- The slopes of Nishi Dake, which form a chain with Mt. Togakushi.

- Momiji and pine.

Changing Epistemologies: From Historical to Modern Views of Togakushi’s Natural Environment

This post takes a look at geological and historical understandings of Togakushi’s natural environment and then considers the shift from one epistemology to another.

The Togakushi mountains are located north-northwest of Nagano City. Consisting mainly of igneous rock, they began forming between 40 million and 27 million years ago through submarine volcanic activity. Gradually, magma protruded upward as layers of mud and sand settled and hardened. Shifts in the earth’s crust eventually pushed the entire region above sea level and through subsequent uplift and erosion, the peaks of Togakushi (1904m) and the neighboring Amakazari (1963m) took form.

The surrounding peaks of Iizuna (1917m), Kurohime (2053m) and Myoko (2454m) emerged later (approximately 17 million years ago) through violent eruptions. Shaped as typical cone volcanoes, their cores consist of an igneous rock known as porphyrite, with layers of sandstone and sediment extending outward.

Below the range, high plains are dotted with hot springs–evidence of magma rolling just below the surface. While the sea now lies just northwest of the region, shells and the fossilized bones of crabs, seal and whale dating back to the early formation of the peaks can still been found.

. . .

The description above of course, reflects a geological understanding of the region. This body of knowledge has been vital in informing policies related to water management, natural disaster response, commercial development and so forth. Before this scientific approach was applied to the Togakushi region however, a preexisting body of knowledge that was also shaped from the mountains guided understandings of the region. Because rice production has long been central to people’s lives, this earlier epistemology concerned agriculture.

Water flowing down from the Togakushi mountains has always been key to the productivity of the agricultural basin below. The immense snow pack that accumulates over the winter in these high peaks melts off in the spring, feeding the area’s streams, rivers, and aquifers.

One stream source in fact, emerges beside the craggy abode of Kuzuryū 九頭龍, the nine-headed dragon who allegedly appeared when the first ascetic reached the range long ago. Indicative of beliefs across Asia, the dragon at Togakushi has long been understood to control the supply of water—from both the clouds and the mountains. Kuzuryū was likewise appealed to for crop water as well as prevention of water-related disasters (flooding, landslides, etc.).

Just as important to agriculture is the sun’s energy. Incidentally, recent scholarship reveals a strong connection between solar worship and the historical layout of the temples and pathways. In his recent book, Gentō no Togakushi (Togakushi’s Winter, 2011), Miyazawa Kazuho argues that some of the oldest religious sites on the mountain align precisely with the direction of the sun’s rays on the summer and winter solstices. The early morning rays of the winter solstice for example, penetrate directly through the torii at Okusha 奥社. Archeological studies have found similar connections at other numinous mountains throughout the country. Moreover, the winter solstice has long been a date in Japan for rituals intended to store up energy to overcome the increasingly cold days of winter.

These are some of the concepts that guided understandings of Mt. Togakushi prior to the modern period. It goes without saying that modern science in general has greatly improved living conditions since then. What is less discernible though is the extent to which these sciences have displaced preexisting epistemologies like the ones mentioned above. In discussing some of the pioneering geologists in Japan during the 1870s, Stefan Tanaka remarks,

“The geological research of men like Milne and Naumann was instrumental in demystifying this amalgamation of the human, natural, and spiritual worlds by bringing in the abstract arena of science… The accounts of Milne’s and Naumann’s expeditions clearly juxtapose the ideas of the locales as superstitious in comparison to their science. In other words, geology turns inherited forms of knowledge into textual forms; practices to ward off disaster became superstitions, a time-concept that relegated ghosts and wonder to a ‘scriptural tomb.'” (New Times in Modern Japan, 2004, 61).

As Tanaka concludes, scientific study brought not only innovation but also value-laden judgments to an entire structure of practices and concepts. Geologic surveys, which were commissioned by the new Meiji government, might additionally be seen as a form of cultural subjugation by the rapidly expanding imperial state over regional populations. And at the same time that belief in the local gods was being swiftly displaced by the “abstract arena of science,” a new powerful deity was being deployed throughout the country. This one, heavily propagandized by the Meiji state, was the emperor himself, as both father to the nation and a living god descended from Amaterasu.

Whether this national project of replacing local beliefs with a centralized belief structure was ever fully realized is of course, a matter of debate. Looking at modern day Togakushi, one can still see priests offering rice to Kuzuryū every morning, alongside a steady supply of coins from visitors visiting the dragon’s shrine. Even the nearby ski lift makes its annual requests for a healthy snow pack.

Reviving a festival

The Hashiramatsu 柱松 (literally, ‘pine trunks’) is an event in which three columns of tied bamboo or pine branches are stood upright and lit on fire. The first to ignite determines the success (agricultural, economic, etc.) of the coming year. Traditionally coinciding with the first day of Obon, it may have also been believed to invite down the local deities and ancestral spirits residing in the mountains. The festival is held every three years at Togakushi and dates back to the late thirteenth century. Well okay, that chronology is a bit misleading.

In the wake of major alterations to religious institutions by the government in the early Meiji period, the Hashiramatsu ended in the 1870s. During this time, the three major temples on the mountain and their cloisters transformed from combinatory sites of Buddhism, Shinto and Shugendo into state-supported Shinto shrines. Shugendo itself was proscribed from mountain sites around the country, which helps to explain the disappearance of this shugen-influenced ritual from Togakushi.

But after a thorough investigation by local scholars of extant sources related to the Hashiramatsu at Togakushi as well as other mountains (where it has continued uninterrupted), the festival has been recently revived. Seeing the Togakushi Hashiramatsu offers a glimpse into the rich symbiosis of religious influences that were historically characteristic of practice at Togakushi and other sites around the country. It may also suggest the future direction of the culture at Togakushi Jinja, given the community’s increasing re-engagement with its vibrant past.

(Click on photos to open gallery mode.)

- The three hashira, one for each shrine, arranged before the ritual. In keeping with one Edo period description, Chusha’s 中社 hashira is composed of bamboo, Hokosha’s 宝光社 is single branches, and Okusha’s 奥社 is a combination of the two. Lines with hanging white paper gohei 御幣 demarcate the inner ritual space, which must be fully purified of bad spirits (mamono 魔物) before the ritual takes place.

- There were several performances preceding the Hashiramatsu. Here are the Togakushi Ninja Taiko players.

- The Shishi Kagura 獅子神楽, performed by a group from Hokosha.

- A third, dramatic taiko performance, performed as a solo by the visiting priest, Sekiguchi San.

- A ritual procession from Chusha down to the hashira. A head priest leads.

- Next in line are a group of visiting shugenja (practitioners of Shugendo) affiliated with Mt. Omine. They blow the horagai 法螺貝 as they approach.

- Four miko 巫子 dancers follow in the procession.

- Banners held high within the ritual space announce both the groups present and the gods invited. Note that the banners display Edo period names (宝光院 instead of 宝光社), emphasizing their former identity as Buddhist temples, not Shinto shrines.

- In order to purify the ritual space, the daisendatsu 大先達 (“great guide”) waves his staff in sweeping motions (not shown here) in order to ward off bad spirits. Immediately after, he recites here a purification prayer (Oharai norito 大祓詞), followed by a chant of the Heart Sutra.

- Two tengu also perform. Tengu, a kind of supernatural mountain beast, often serve the role of frightening off bad spirits from a ritual space.

- A ritualized “three sword dance” (sanken no mai 三剣の舞) is performed. Their performance represents a form of genkurabe 験比べ. This “competition of powers” (as the term translates) historically often took place at shugen sites after practitioners emerged from periods of confinement in the mountains. During these periods, they built up special powers which they then demonstrated in competitive fashion before an audience. It is debatable (based on extant sources) whether or not these competitions took place at Togakushi. Their inclusion here reflects knowledge of these types of performances taking place at similar shugen events.

- The “self-purifying dance” (身滌の舞), a second, solo dance also performed in genkurabe fashion.

- After stoking the base of each hashira (not shown here), flames engulf the bamboo hashira first, making loud popping sounds as hot air escapes the bamboo shoots.

- With all three lit now, the shugenja, led by the daisendatsu, circumambulate the fire. Control of fire has historically been an important aspect of Shugendo.

- A shugenja waves a gohei pole over spectators as a purification ritual for their behalf.

The ceremony ends with the head priest seeing off the mountain deities and spirits as they return to the mountain.

Again, the event is held only once every three years, so if you get the chance, be sure to check it out in 2015!