After about a year of requesting to view archives at Togakushi Jinja that are relevant to my research, I finally finagled my way into seeing a number of them on my last visit before returning to the States.

These documents were archived and catalogued in the 1960s and have since sat in a storage shed at the shrine, for the most part untouched. A huge thanks to local scholar and priest, Futazawa Hisaaki 二澤久昭, who spent hours rummaging through them (apparently in disarray) and then further hours helping me to decipher some of them. Futazawa-San by the way, descends from one of the Edo period cloisters (shukubō 宿坊) and has converted his into a wonderful Japanese inn and serves delicious food.

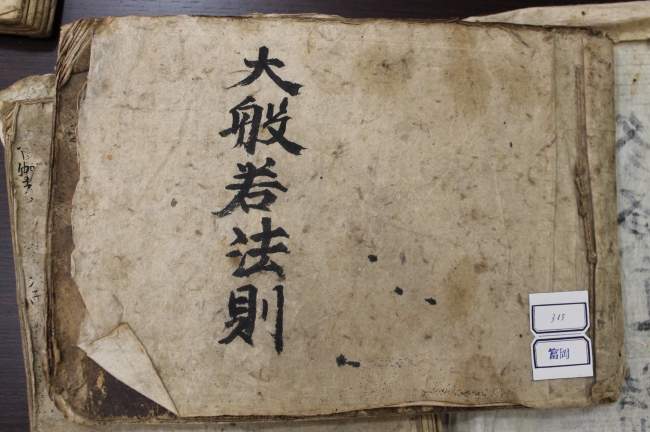

Here are samples of some of the texts we checked out.

These first three images are from a text titled the Dai hannya hōsoku 大般若法即 (Regulations of the Great Heart). I haven’t looked closely at it yet but the title refers to Prajñāpāramitā literature and the nature of the text is ritualistic. It’s not listed in the catalog so was a surprise to find.

The date on the last page here reads Keichō 慶長 3, or 1598.

The two volume set below, titled the Shugendō hiketsu hōsoku 修験道秘決, was the most exciting text of my find and will probably factor into my assessment of Shugendō at Togakushi during the Edo period. Its undated but based on the content, must have been composed in a hundred year period between the 1720s and 1818.

This is a registry of Togakushi-san’s from 1814 (Bunka 11). It lists 32 Shugendō households affiliated with the mountain at this time.

The information for each yamabushi 山伏 presented here includes his rank, year of birth, year of tonsure, temple location and name, and his affiliated Togakushi cloister.

Often these yamabushi would serve as disciples to the priests of the mountain and eventually succeed them. For this reason, Shugendō became central to the identity, practices, and thought of Togakushi during the Edo period (I argue), despite its subordination to the Tendai Buddhist institution at this time.

At the end of the Edo period, there was a major drive at Togakushi to strengthen its branch of Shugendō. This next text, titled the Togakushi-san Kenkōji kanjō saikō gan 戸隠山顕光寺灌頂再興願 was composed by the mountain’s chief administrator (bettō) in 1861.

The effort only lasted a few years, as the temple-shrine complex was converted into a national shrine at the beginning of the Meiji period.